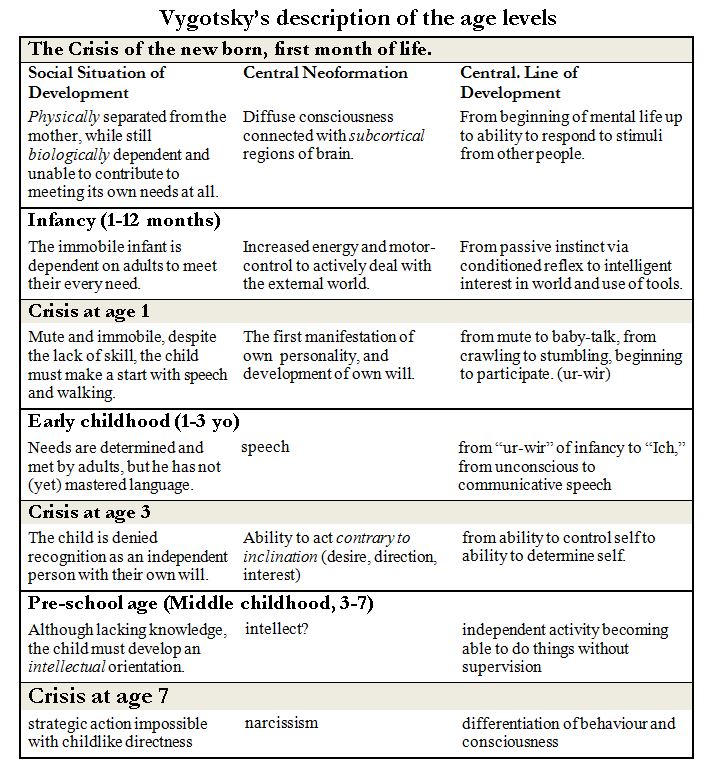

Vygotsky saw child development as consisting of passing through a series of periods of stable development, namely, infancy, early childhood, pre-school age, school age and puberty. These periods of stable development are punctuated by periods of crisis: at birth and at the ages of 1, 3, 7 and 13.

Vygotsky names these stages in terms that evidently made sense in the USSR of his day, but the periodisation essentially depended on the occurrence of specific structural transformations in the child’s relation to their social environment and correspondingly in their mental life. He claimed that under different social conditions these transformations will still take place, but will happen “differently,” and up to a point, at different ages. For example, referring to the crisis at age 7, he says:

“Facts show that in other conditions of rearing, the crisis occurs differently. In children who go from nursery school to kindergarten, the crisis occurs differently than it does in children who go into kindergarten from the family. However, this crisis occurs in all normally proceeding child development. ...” (p. 295)

What is important in every case however, is the concept Vygotsky proposes for each of the structures and transformations. That child development takes place very differently in different historical circumstances, is not just a matter of empirical fact, but rather points to the need for concepts which allow us to understand the route by which cultural factors, which can be empirically determined, participate in the development of the child, thereby allowing us to understand the mechanism whereby the culture and institutions of a society are reproduced from generation to generation. The fundamental character of the structures with which Vygotsky is concerned forces us to consider that the same series of transformations may be experienced by children developing in any society, though in every case, they will be experienced differently, and the outcome will be different.

There are several unique concepts which Vygotsky introduces, understanding of which is the main thing we have to look at today. I will now give you a quick sketch of these, and then perhaps we can clarify these concepts in discussion.

The first and most important concept is the Social Situation of Development.

“... at the beginning of each age period, there develops a completely original, exclusive, single, and unique relation, specific to the given age, between the child and reality, mainly the social reality, that surrounds him. We call this relation the social situation of development at the given age. The social situation of development represents the initial moment for all dynamic changes that occur in development during the given period. It determines wholly and completely the forms and the path along which the child will acquire ever newer personality characteristics, drawing them from the social reality as from the basic source of development, the path along which the social becomes the individual” (p. 198).

Vygotsky conceives of the social environment in which the child finds itself and the relationship of the child to other people, not just as a collection of factors, as influence or resource or context or community, but concretely as a predicament.

The child begins life utterly helpless; even the cortex of the brain does not yet function sufficiently well to perceive the figure of objects or people, or even distinguish the child’s own body from its background; the child is unable to contribute to meeting or even determining any of its own needs. At the end of the process, if each of the periods of stable development and crises have been successfully negotiated, the child has become a fully mature member of the wider society, able to determine and meet their own needs in a manner consonant with their social position, aware of other possible social positions, taking moral responsibility for their actions, and participating in the reproduction of the culture and institutions of the society.

At each successive stage in the child’s development the child becomes able to perceive that the very situation through which their vital needs are being met, has ensnared them in a trap from which the child can only emancipate herself by striving in a way that stretches the capacities that they have at the given stage of development. In the case of a stable period of development, this striving brings that central function to maturity and makes the social situation of development redundant, bringing into being a new predicament. In the case of the periods of crisis, with its striving the child forcibly breaks from the predicament and opens the way directly to a new period of stable development in a new mode of behaviour and interaction.

The predicament is therefore contained in the way the child’s needs are being met through the adults related to the child, which lock the child into certain modes of activity which they are capable of sensing, at one point as a mark of respect or a degree of freedom, but at another as a limitation, and even come to see as a kind of insult, the transcendence of which becomes a need and a drive in its own right; but they are not yet capable of transcending that limitation, and their efforts to do so are frustrated. The mode of activity through which the child’s needs are being met is created in response, on one side, to the expectations the adults have of the child, and the resources they have acquired from the culture, and on the other side, to the child’s behaviour and age, according the child’s capacities. Numerical age may be a factor, simply because institutional norms impose age level expectations on the child irrespective of the child’s actual level of functioning.

As the child develops within the social situation of development a contradiction develops. Whereas the child’s needs have been satisfied up till now through the existing situation, due to the child’s development, the child becomes aware of new needs, new needs which presuppose the child occupying a new role, and a corresponding change in the social situation. An infant may be quite happy having its mouth stuffed with food ... up to a point, but they soon feel the need to have a say over what is put in their mouth. They need to disrupt the situation in which absolutely everything is done for them.

So this ability to perceive new needs does not yet mean to be able to satisfy them, both because they do not yet have the ability and because the adult carers do not treat them as a child who has the ability. They are stuck in this situation which they have begun to see as a restriction, even though it is the situation in which their needs are being met. For example, a child might be angry and wants to defy their mother, but at the moment they simply can’t overcome their own inclination and their mother finds it easy to manipulate them. In this circumstance the child may become defiant and refuse to do anything, so as to free themselves from manipulation by their mother by developing their own will and letting their mother know that they have a mind of their own.

It is this striving to take on a new role and change the situation which is what actualises development. But the development can only be actualised if the adult carers respond by entering into the new mode of interaction with the child. The child perceives the situation as a constraint and strives to overcome it, and thus by implication, the overcoming of these constraints which fall within the child’s capacity to perceive, is also a key need of the child, a drive which is not facilitated, but frustrated by the social situation which created it. If the child does not feel a need to overcome these constraints on the determination and satisfaction of their newly-perceived needs, or does not strive to overcome these constraints and emancipate itself, then a pathological situation exists and the child will not develop. For example, a young teenager who never feels any need to criticise the views and ways of the own family and their teachers will never fully develop as an adult and take their own position in society.

Notice that the child must become aware, at whatever level it is sensible to speak of a child of the given age being aware, of the limitations of their present position; that is, they must in some way be able to visualise a different role for themselves. The conditions for becoming aware of such a role are created by the current social situation of development, but there are always limitations on the ability of a child to see what could be, but is not yet the case.

Thus we have an abstract definition of the social situation of development which tells us how to understand the infinity of relationships around the child so as to grasp concretely how the social environment determines and affords development of the child. A society only offers a finite number of distinct roles for people according to their life course. These will be different in each culture, but every society has such roles with their rights and expectations for everyone from the maternity ward to the retirement home. Each of these life stages constitutes a viable form of life in the form of specific relationships between a person and those around them.

As a general concept, the driving force of the development is the predicament created by a gap between the child’s manifest needs and the current social means of their satisfaction. This way of conceiving of the social situation of development is universal, but in every single case the situation is different because the adults providing for the child’s needs do so differently in different cultural circumstances, and have different expectations of the child and will react differently to the child’s behaviour, not to mention the indeterminate impact of differences in the diet and physical conditions of existence that the adults provide for the child. For example, the infant may grasp for her mother’s breast, but the mother may or may not respond; the child’s predicament is the same, but the outcome is different. Actualisation of the social situation of development is different in every different social and historical situation, and the course of development is different in each case. In that sense, development is culturally determined. But in each case, in understanding the factors determining the course of development, we will look at this contradiction between the level of the child’s development more or less corresponding to the manner in which the child’s needs are being met, and the constraints this mode of interaction imposes on the child, insofar as the child is capable, at the relevant stage of development, of intuiting those constraints and strives to overcome them. For example, the child who proudly turns up at school, ready to take on their new role outside the immediate care of their own family, but, unable to distance their consciousness from their behaviour and adopt an intellectual disposition, will not only fail at their schoolwork but will suffer terribly in the playground and will feel an intense need to master strategic behaviour and adapt to the demands of life at school. This can be a traumatic time for any child, but it is only thanks to being thrown out of the nest, so to speak, that this development is made.

Vygotsky gives an example of a social situation which demonstrates how one and the same situation may bring about different development outcomes according to the child’s age. A single mother had three children, but had become dysfunctional due to becoming a drunkard. The oldest child made a development, acting well above his age, taking over the role of head of household and looking after his mother as well; the middle child had been close to her mother and could not adjust to her wild behaviour and her development suffered; the youngest child did not even notice the change, so long as her basic needs were being met. This shows clearly how the Social Situation of Development is about the relationship of child’s needs and awareness to the circumstances surrounding them.

Neoformation: this rather strange word is used by Vygotsky to mean a psychological function, or more precisely a mode of interaction with the child’s social environment including a specific mode of mental activity implied in the given type of social interaction in the given social situation. A neoformation is so-called because it newly appears at a specific stage of the child’s development, differentiating itself from other functions and enabling a new mode of social interaction.

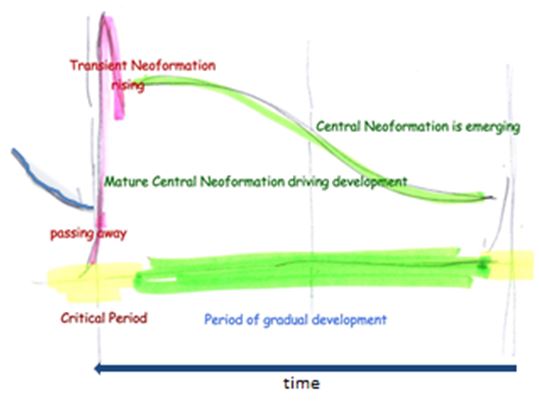

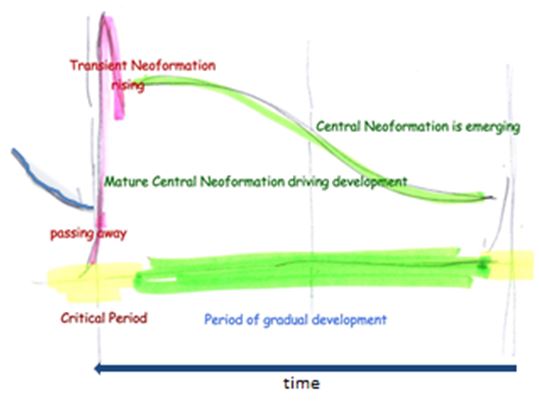

Each age-level of development of the child is characterised by a social situation, with its specific predicament, and one neoformation above all others, plays the leading role in restructuring the mental life of the child, which Vygotsky calls the central neoformation.

In the case of stable periods of development, the central neoformation gradually differentiates itself in the first phase of the period, and then in the latter phase, drives the restructuring of the child’s behaviour and eventually makes the social situation of development redundant by overcoming the former constraints, generating new modes of interaction and setting up a new predicament. The central neoformation does not disappear, but continues to develop and play its part in the child’s activity, but no longer plays the central driving role in development. Later it will develop along a peripheral line of development.

“These neoformations that characterize the reconstruction of the conscious personality of the child in the first place are not a prerequisite but a result or product of development of the age level. The change in the child’s consciousness arises on a certain base specific to the given age, the forms of his social existence. This is why maturation of neoformations never pertains to the beginning, but always to the end of the given age level” (p. 198).

In the case of the critical periods of development which mark the transition from one period of stable development to another, the central neoformation forces a break from the old relationships and lays the foundation for a new social situation of development but it is transient, but in the normal course of development it fades away and will reappear later only under extreme conditions. These are called transitional neoformations.

“The most essential content of development at the critical ages consists of the appearance of neoformations which ... are unique and specific to a high degree. Their main difference from neoformations of stable ages is that they have a transitional character. This means that in the future, they will not be preserved in the form in which they appear at the critical period and will not enter as a requisite component into the integral structure of the future personality. They die off, ...” (pp. 194-5)

This means that the kind of negativity which children resort to during critical periods in order to break into the new relationship will fade away and will generally only reappear in the event of a breakdown in the new situation. Also, during the very early phases of life, infants and their parents often manifest very advanced modes of interaction, but these are not based on cortical functions of the brain and are not going to go on to be the foundations of mature psychological functions, and fade away as the critical phase after birth is passed.

In its development from a helpless newborn to a mature and responsible young adult, the child must pass through a series of age levels, each of which constitutes a viable form of social practice, a Gestalt. At each point in this development, the child is able to utilise only those neoformations which have been developed so far, pulling herself up by her own bootstraps, so to speak. Each chapter in this story involves transformation of the mental life and mode of interaction of the child from one whole, viable form of life to another. Thus at each age-level there is a central line of development which is the story of how the central neoformation of the age level differentiates itself from the psychic structure and brings about a new constellation of psychological functions, transforms the relationship between functions, stimulates the development of others, while suppressing still others, transforming cause into effect and effect into cause, turning means into ends and ends into means. The central line of development in each age level is driven by the requirements of development of the central neoformation. But, at the same time, peripheral lines of development, subplots so to speak, continue, sometimes in support of the central lines of development, other times continuing the work begun in previous age levels, refining and strengthening functions which are no longer the driving force of development. The central line of development is the story of how the child overcomes the predicament contained in the social situation of development and leads into a new predicament, and how the central neoformation restructures the mental life of the child and their relationship to the social environment.

“... at each given age level, we always find a central neoformation seemingly leading the whole process of development and characterizing the reconstruction of the whole personality of the child on a new base. Around the basic or central neoformation of the given age are grouped all the other partial neoformations pertaining to separate aspects of the child’s personality and the processes of development connected with the neoformations of preceding age levels. The processes of development that are more or less directly connected with the basic neoformation we shall call central lines of development at the given age and all other partial processes and changes occurring at the given age, we shall call peripheral lines of development. It is understood that processes that are central lines of development at one age become peripheral lines of development at the following age, ...” (p. 197)

Thus the age levels are characterised by the specific mode of interaction which arises on the basis of the social situation thanks to the central neoformation which moves to the fore and matures in the given age period along the central line of development for that age period. Since each of the phases of development entail biological changes in the organism as well as institutional expectations taking account of historical experiences of the society, the age levels do implicate regular years of age, but they are defined not by age, but by the central neoformation of development in the age level.

Stable age levels are periods during which the growth of a central neoformation takes up a central role in development in and through its becoming a mature and continuing part of the child’s psyche. In critical age periods, the child forcibly breaks from the former social situation of development by the premature exercise of increasingly developed forms of wilfulness, manifested in forms of negativism.

These forms of negativism, which rest on the child’s striving despite everything to overcome the frustration of their drive to do that which they cannot do, disrupt the former relations and open up conditions for a new period of stable development, in which the negativism of the critical period has to be let go.

Vygotsky says that during the periods of stable development, the changes in the single neoformations drive the development of the whole, but during the critical periods of development, it is the change in the whole structure of the psyche which determines the changes in the separate neoformations and relations between them.

“At each given age period, development occurs in such a way that separate aspects of the child’s personality change and as a result of this, there is a reconstruction of the personality as a whole – in development [i.e., during the critical periods] there is just exactly a reverse dependence: the child’s personality changes as a whole in its internal structure and the movement of each of its parts is determined by the laws of change of this whole” (pp. 196).

Thus, during the stable periods of development, the child’s personality undergoes gradual change along the central line of development as the central neoformation gradually matures and restructures the entire personality, but as it matures, gradually comes into conflict with the situation, unable to find a satisfactory resolution. During the critical periods, the whole personality undergoes a structural transformation and all the psychological functions are rearranged according to the success of this transformation towards a new relationship between the child and their environment. At the beginning of the critical period the child exhibits negativity in relation to its current role, and then in the latter phase of the critical period, the child exhibits instability in adoption of its new role.

The child begins totally undifferentiated from their mother, physically, biologically, psychologically, intellectually and socially, and their psychological functions are also undifferentiated. So long as behaviour is not differentiated from affect, the child is a slave to their own feelings, for example. So long as the youth does not differentiate themself from their social position they are unable to take moral responsibility. It is only by the complete differentiation of the various psychological functions, that the young person can gain control over their own behaviour and participation in society, and differentiate themself as an individual from those around them. It is only by this complete process of differentiation that the individual can actually become a real part of their society, actually contributing to the production, reproduction and transformation of the culture and society.

Thus the process is contradictory in the sense that integration into a truly human society presupposes a process of differentiation of the individual. The whole process of becoming human is driven, from beginning to end, by the striving of the child to overcome the limitations to its self-determination and emancipate itself from imprisonment by its own drives. This drive for emancipation then proves to be the only genuinely human drive, the drive which knows no end and transcends all barriers.

The Zone of Proximal Development is the most widely known and used of Vygotsky’s concepts. There are many things that a child may see others around them performing, which no amount of coaching or trying will allow them to even imitate. There a range of psychological functions, however, between those which, on the one hand, the child is able to master even without assistance, but on the other hand, the child cannot manage even if given assistance. The range in between these two limits is called the Zone of Proximal Development, within which he child can manage the activity if given assistance. According to Vygotsky these are the functions which lie within the child's reach and the child can be taught. Trying to teach the child something which lies beyond their ability to achieve even with assistance is a waste of time, and will have to wait until the child has further matured in their current situation. If two children are judged to be at the same level according to what they are able to do unaided, but one child is able to achieve more than the other when given assistance, this indicates to the teacher the additional potential of the child in terms of their as yet untapped development.

If we know what is the central line of development at a given stage in the child’s development, and the identity of the central neoformation, then what conditions or modes of interaction of the child will promote that line of development and ensure its successful completion? At each level, the child’s personality undergoes a reconstruction, and one function above all others is destined to play the leading role in that reconstruction. If instruction can bring about development of that function then the development of other functions will follow as a matter of course. On the other hand, there are always peripheral lines of development which play only a secondary role in the child’s overall development, that is, the reconstruction of their personality in preparation for adopting a new mode of interaction with their environment.

So it is clear under these circumstances that it is the position of this central neoformation in the Zone of Proximal Development which is crucial if the teacher is interested in assisting the child in making a development, rather than in simply learning to do more things. On the other hand, during the long stable periods of development, that is precisely what the child needs. The central line of development is the maturing and consolidation of the central neoformation which characterises the whole stage of development. And during the early phase of that stage, while a child is still stabilising the neoformation of that stage, operating at the higher level is beyond the child’s imagination and reach. This only becomes possible when the central neoformation has matured.

So during the stable periods of development, the social situation of development obliges the child to strive to master the psychological functions lying within limits imposed by her social situation of development and as a result of this striving, the central neoformation develops and leads the whole process of development. Vygotsky assumes that carers and teachers will be aware of those psychological functions which lie within the Zone of Proximal Development, and which Neoformations are central and which peripheral. Appropriate instruction which promotes the striving of the child and the differentiation and growth of the central neoformation will assist development, whereas efforts to interest the child in other activity, which involves peripheral lines of development or are beyond the child’s age level of ability, will not be expected to bring any benefit in development.

During the latter stages of that stable phase of development, the child begins to be able to perceive new possibilities, and by assisting the child, the teacher or carer may be able to see that qualitatively new functions are coming to be within the child’s reach, and instruction should be directed at encouraging these new forms of activity.

It is here that Vygotsky’s concept of the “Zone of Proximal Development” is relevant. Instruction may lead development, if and only if instruction assists the child in promoting the differentiation of the leading neoformation. Vygotsky proposed that what the child can do today with assistance (for example by asking leading questions, offering suggestions) or in play (which allows the child to strive to do what they actually cannot yet do), they will be able to do tomorrow without assistance. The desired “flow over” to different functions resulting from success in performing the given task will occur only if the intervention has promoted the central or leading neoformation. Otherwise, teaching by assisting the child with a task may help them learn that task, but there will be no flow over to development. In that sense, we could introduce into the concepts Vygotsky uses in this work the idea of “leading activity,” that mode of activity and social interaction which promotes the striving of the child in exercise of the central neoformation of the age-period.

For example, a 3-year-old who is showing the first signs of being able to carry out tasks without supervision would be encouraged and supported with great care because the development of this capacity for independent, unsupervised activity is the central line of development, in Vygotsky’s view, for the period of middle childhood.

During the periods of critical development however the situation is different; the child is trying to rupture the social situation of development and create a social position for themselves in a new social situation. The child’s behaviour in these periods of crisis is disruptive of the existing relationships. The child’s carers need to understand what lies behind the child’s behaviour and assist the child through to the new social situation. Again, this is a question which will exercise the skill and art of the educator and carer, and Vygotsky did not live to offer advice on this matter beyond helping to give us an understanding of the dynamics underlying the child’s behaviour and development.