Writing the story of my life has been a happy task. It was really inspired by Betty who wanted me to tell her all about the family. I felt that the most efficient way to do this would be to write it rather than attempt to speak it.

‘Memory unlocked the door’ and I looked down a long avenue, right back to when I was four years of age. Starting with a brief account of the coming of my parents to Australia, I then began on my own history – the first day at school. It was like going through a gallery of pictures, all of them a little faded, but memory gradually put back all the colours. one thing led to another, and before long, the pieces began to fit into a pictorial mosaic.

My life has always been sheltered by love, no matter how stormy the outside circumstances. Going back to this period to incorporate it in this diary, I realise more than ever before how much I owe to my home environment, especially to my Mother and Father, and my sister May. In the attempt to put it all down in words, I have lived it all over again, though there has been a little sadness arising from it – the fact that I did not appreciate it as fully as I might have done and the futile longing that I wish I could have the chance all over again. I suppose this is the most common reaction – that children, when they have lost their loved ones, realise they could have more fully expressed their love. Strange, we “never prize the violets, till the lovely flowers are done.”

As this is a diary, mostly of my own personal life, it has been necessary to use the personal pronoun very often. This I regret, but I have not the ability to do otherwise.

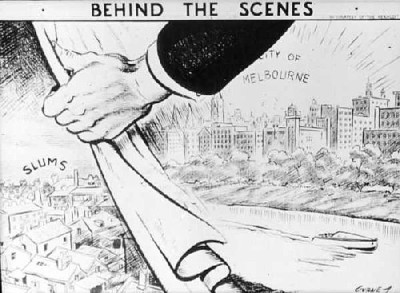

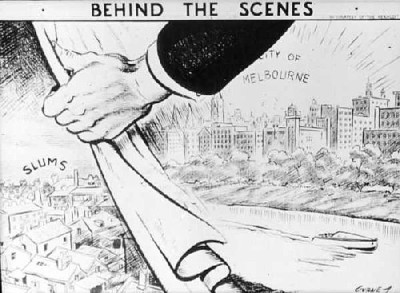

In the two great Social Ventures in which I was vitally interested it may seem that I claim too much for myself. Also, I am sorry, for though I was instrumental in bringing both to birth, I realize very frankly that neither would have succeeded without the dedicated support of those who caught the vision. It is obvious that the idea of saving slum babies would have been just an empty dream but for the enthusiasm of the young men and young women, and through the whole-hearted support of the Methodist Church, institutions of the Housing Commission was possible only because the inspiration set on fire the men and women who attended what was called “The Barnett Slum Study Group.” To all of them, “I lift my hat.”

The story of my pilgrimage through the years.

My father and mother were born in Cornwall. They left St. Day in Cornwall on 31st May, 1874, and sailed from Liverpool on 4th June in the “Great Britain.” In 1853 the “Great Britain” had made an historic trip to Australia. It was the first auxiliary steamship to complete the voyage.

At the age of eight, Father went to work in a mine and his schooling (for which his Mother had paid two pence per week) came to an abrupt end. He could, however, read and write, but his spelling was absolutely phonetic. He was naturally good at figures, and when working later as a quarryman, would calculate the cubic contents of a dray-load of stone, more quickly in his head than I could on paper.

After they were married, my Father, while working in the shaft of a mine, was, by a premature explosion, blown up several feet, and then fell down the shaft. Almost every bone in his face was broken, and thereafter he wore a beard. As he regained consciousness, a rescuer was pressing a glass of brandy to his lips. He impetuously knocked it away. As a youth, he had frequently taken too much liquor, one time being so much under the weather that his Father wheeled him home in a wheelbarrow. Thoroughly alarmed by his son’s danger, his Father said that he would take no more liquor if his son would agree to do the same. My Father agreed, thinking that my Grandfather would not be able to keep his resolution, but when he found that his Father was fully determined, he too decided to keep the pledge. As he was converted later in the Methodist Church, there is no doubt his religious convictions greatly strengthened this resolve. As a result of the accident down the mine, my Mother persuaded my Father to give up mining and they decided to emigrate to Australia.

They brought with them their two daughters, Ada agreed three, and Mabel who had her first birthday on the water.

Landing in Melbourne on the 29th July 1874, they settled in East Brunswick where they lived for the rest of their lives. There they had five more children. Following May there was Jack, then Ethel and a twin brother, and following them were more twins, Percy and I. Ada died soon after arrival and Ethel’s twin and my twin did not live long after birth.

As my Father was not permitted to work down a mine, he became a Quarryman, the work for which mining had evidently fitted him.

He prospered sufficiently to buy a small single-fronted cottage in Linden Street, East Brunswick on land 78 feet frontage and by about the same depth. Later, the cottage was doubled by adding two rooms on the West, allowing for a passage in between the old part and the new addition.

We had the best house in the street now, double fronted with twin gables. In the rear of the Eastern gable was a small louvre door, through which I used to crawl to get eggs from the sparrows’ nests under the roof. I was quite dark there, so I would take an old bull’s eye lantern (lit by a candle inside) to show me where to step over the ceiling joists. Even in those days there was a fear of an invasion by the Russians, probably the aftermath of the Crimean war. If they came, I would hide under the roof, where I was sure they would never find me.

But I was sure that they would never be able to land in Port Phillip Bay, because we had naval protection – an old gun boat, called the Cerberus. Its guns were said to be so near the waterline that when they were fired at an invading ship the cannon balls would hit at the water’s edge, so that it would quickly sink. Thus were my childish fears banished.

Our dining room was looked upon as immense, being 17 feet by 12 feet. (The standard room in workers’ houses was generally 12 feet square.)

The passage from the front door finished at the door opening into the dining room. When my brother Jack became a carpenter, he added the most compact all-purpose room I have ever seen. It was about eight or nine feet square, and was attached to the South-east corner of the dining room. As one entered the door, there was a hand-painted sheet-iron bath immediately on the left, stretching to the East wall. On the East wall were two wooden troughs and the copper. On the south wall was a coal stove.

As the troughs had removable wooden tops they served as table tops at breakfast time, which was very handy, as the food was cooked on the adjacent stove.

This room was also a very convenient bathroom, the water being heated in kerosene tins on the stove, and then lifted across to the bath some five or six feet away. On one occasion, as my Mother was lifting a tin of hot water to the bath (I was sitting on the edge) she slipped, and she poured the hot water all over my legs and feet. Though the hot water was hot enough to make my legs a little red, fortunately it was not boiling, though I let out a yell that was ‘hark to the tomb’. I recovered quickly, and we celebrated by Mother, May and I going down to St. Kilda for the afternoon. The weekly hot bath was always on Saturday, hence the possibility of going down to the beach.

Other than breakfast, all meals were had in the dining room. We were rather proud of the dining room, but as it had a skillin my brother remedied this defect, when he built the kitchen-cum-bathroom-cum-laundry. This improvement gave the family much pleasure, for things hardly won are always the most appreciated.

We called the house by a Cornish name “Pendruver.” The name was painted on a strip of galvanised iron in dark red letters outlined with gold, against a background of dark green. Ours was the only house in the street that had the distinction of a name.

I can still vividly remember the furniture we had. In the “front room” was a small piano, much prized, and used a good deal. There was also a “what-not,” a three cornered piece of furniture consisting of a small group of shelves placed one above the other on which cherished ornaments were placed. The one thing I remember best was a bull-dog in white china with a black nose. Naturally, the “what-not” was placed in the most sheltered corner of the room, generally diagonally opposite the door.

There was also a dainty oval table, very beautifully inlaid.

In the dining room we had a painted drain-pipe in the corner, which was always filled with pampas grass, a big clump of which grew in a corner of the front garden. When pampas grass grows old it becomes very soft and fluffy and highly inflammable. One night I stood near it with a lighted candle, and as quick as lightening it caught fire. I was scared stiff because I knew that our house being weatherboard would burn like matchwood. I was afraid to touch it with my bare hands, so I pulled my coat sleeves over them, and quickly patted the fire out. When the family knew what risk we had run we were all very thankful.

One possession we greatly prized was a tea-set, with a cornflower design. I think it must have been very good china, for though it was always in use on Sundays and when visitors came, some of the cups and saucers are still intact.

Though our house was easily the best in the street, we were ashamed of the street itself. It was very narrow, looking back I should say not much wider than twenty-feet. Opposite to us was a tumble-down shack, and next to that a row of single-fronted cottages built on a frontage of about fifteen feet each. During the depression following the land boom, they were let at 4/6d. per week each. This was in accordance with the working mans dictum that rent should not be more than one day’s pay, (for those in work) for the unskilled labourer it was then 5/- a day.

But it was not so much the street itself, but the approach to it, about which we were sensitive. In ran into a right-of-way at the top end, and it was galling to our pride to bring visitors down this right-of-way to enter our street. Nevertheless, despite the shabby approach to the Street, I spent a very happy childhood there in a family that was very affectionate.

Betty took me recently to see the home of my birth. The area was so changed that it was hardly recognisable. Our old home has been replaced by a factory, and several new houses have been built on the vacant blocks. The row of cottages opposite has been repainted and looks vastly superior. In a word, the whole street has had a face lift, but I missed the sentiment that through the years was attached to the old home. Probably this whole area with its out-of-date rights-of-way (belonging to the pre-sewerage era) will have to be demolished and re-planned.

One of my happiest recollections as a child was the way we celebrated Christmas day. Mr. and Mrs. John Jenkin were great friends of my father and mother arriving in Melbourne somewhere about the same time as they did. They always invited the whole family up to their place on Christmas Day. They had a very nice home in Barrow Street, Brunswick built in the centre of a four-acre block, the rear portion of which was let to Chinese for a vegetable garden. The Jenkins house was surrounded by orchard and garden. The fruit, of course, was a sheer delight to a boy – fruit of unending quantity and of that delicious flavour when it is picked straight from the tree. There was a cow always a famous milker, and cream was laid on. After a real oldstyle Christmas dinner, we rested awhile. Then races were arranged for the children down a curved path that ran to the front gate, and of course every runner got a prize.

There was a circular pond in the front garden, full of gold fish. As there was a fountain in the middle, it was a source of never failing interest, all the more so when one of us would fall in.

After a very tempting Christmas tea, there were the old-fashioned card games of grab and quartets, in which we would join as soon as we were old enough.

When it was time to go home, we were thoroughly tired, but home was two miles away – no trams, no cars, no buggies – just shanks pony. But it was worth it. Even now as I look back, I get quite nostalgic about the happy care-free days of childhood.

All these dear folk have gone to their reward, one of the daughters Edie, being the sole survivor of the original family, and she was ninety years old a few days ago. Her elder sister, Abbie, married Will Phillips. They too have passed beyond the veil, leaving three lovely children, Jack, Ron and Ida, all of whom carry on the old traditions of kindness and the hospitality of the old family. I am grateful that they are still friends of mine.

When I was four and a half years old, I went to the State School situated in Albert Street, Brunswick, known as Hayden’s (after the headmaster), and numbered 1213. It was practically a mile from home so my sister Ethell and I took our lunches (Jack and Mabel by this time having started work,) I can still vividly remember my first day at school. I was terrified, and cried so bitterly that my sister had to come and sit with me until I grew used to my strange surroundings. I was in the babies’ class (really built for tiny children) and as Ethel was nearly fours older than I, and tall and lanky, she sat with knees practically under her chin. The memory of that day is still grievous unto me.

Brunswick at this time was not sewered, is mostly flat, the gutters most of the time held stagnant water, which was swept away once a week by Council men with huge brooms. They also had a short-handled three-cornered hoe with which they would root out the weeds growing in between the stone pitchers which formed the gutter.

Sometimes I fell into one of these steep slimy gutters, which was an adequate reason for my sister to take me home to get cleaned u~ by which time we would be too late to go to school. On one occasion I slipped into the gutter which was, of course, an excuse for returning home. On the way, my trousers dried and it looked as if there was no apparent reason why we should go home. At the instigation of my sister, I straddled an evil-smelling portion of the gutter, she took me firmly by the shoulders, and pushed me down into the slime. We then both went home, and had the day off, much to the annoyance of my Mother, for my trousers had practically dried the second time.

Soon after I went to school I fell in love. She was a lovely creative fair skin, the most beautiful flaxen hair, and eyes as blue as the sea. When I first saw her, she was skipping on the asphalt in front of the Eastern end of the school. I can see her now, her lightfeeted skipping up and down, her hair flying in the wind, and her eyes dancing with delight. I was overcome with admiration, and loved her at first sight.

When I went home after school, I told my Mother all about her, how lovely she was, and how I loved her. I never spoke to her; I was too thunderstruck. I was about five years’ old, she about six, and a grade ahead of me in school. When she moved up into the next grade she left the main school and went down to the “Adjunct” a quarter of a mile away. I never saw her again, though the vision of’ her has remained with me ever since. I wonder if she happily married.

About this time the man next door took his children and me for a drive in his spring-cart to Heidelberg. It was an extremely hot day and he pulled up outside an hotel, which he entered forthwith, and came out with a glass of beer for each one of us. I never tasted such a lovely drink in my life.

When I returned home, I told my Father all about it. He was so angry that he wanted to jump the fence and tell the neighbour what he thought of him. But my Mother restrained him. But I shall never forget the taste of that beer.

When I was about ten years old, I went down to South Melbourne to meet an old school friend who had gone there to live. After a swim, we made our way to the tram. I was wearing a blue Galatea sailor suit with an outside pocket. As I was about to step on the tram, I found all my money was missing. It had evidently slipped out of my pocket and would have been hidden in the sand. So I went up to a lady passing by, told her my story and asked her would she kindly give me enough money to pay my fare home. She went for me like a pickpocket, and so frightened me I started to run, up Elizabeth Street, along the Royal Parade to Sydney Road, stopping every now and then to get my breath. I had learnt at school that exercise made your muscles grow, so, going down Edward Street, Brunswick, I stopped and felt the calves of my legs to see how much they had grown. I was tremendously disappointed that the long run had made no difference whatever.

As a small boy I often took my Father’s contributions to his Lodge down to the home of the Secretary – a venerable old gentleman with a thin straggly beard. As I would wait for him to enter the payment in the Lodge book, I was invariably fascinated by a picture on the wall. I fancy it must have been some form of Lodge Certificate. At the top of the certificate was the picture of an immense Eye with the words “Thus God seest me.” It used to awe me, and gave Me a great fear of God, the Eye that saw everything and from which we could never escape.

It is a good thing that such teaching of God as a God of fear, is being replaced by the truth that God is love.

It was the custom in those days for school children to wear long black stockings to above the knees and kept in position by elastic garters. (The widgies seem today to have resurrected this style).

One of the problems that arose, is that, in falling over, one generally tore a hole in the knee of his stocking. To make it practically indistinguishable I would rub some Day & Martin’s blacking (Nugget was unknown in those days) on the knee behind the hole, which would then pass detection but for the closest inspection.

I do not remember being very interested in school lessons until I was in the Upper Fifth Class under a typical school “marm” – Miss. Rennie. Much to my amazement I won a prize for history which seemed to arouse my interest and the desire to do well. Despite a stern exterior, Miss. Rennie had a kind heart. Sometimes she invited me down to her place for tea, which always proved a very enjoyable affair. She never called me “Oswald” but always called me “Fred.” The only one in the world who ever did so.

I was put into the sixth grade when I was ten Years old, and here I stayed till I was fourteen. Our teacher, Mr. Sam Rowe, was much beloved. He was short and stout, with mutton-chop whiskers, and sported an extraordinary bell-topper, one rather squat, which suited his figure, and was often used as the “model” in model drawing. For many years after our school-days were over, many of the old scholars on the occasion of a back to Brunswick celebration would write to the Press and tell of the extraordinary influence that Mr. Rowe had on them. For many of us he was a most inspiring character, and had tremendous effect on the formation of our ideals. He was the most gifted and most loved teacher I ever met and I cannot think of’ him without a feeling of exceptional affection.

I was under Mr. Rowe for three years, and happy and fruitful years they were. It meant going through the set programme with him three times in that period. In particular, English was thoroughly taught, parsing and analysis, derivations, prefixes and affixes, so that we got a pretty clear understanding of the structure of sentences, and the basic meaning of most of our English words that were in common use. This part of my education I thoroughly appreciated, even more so as the years have passed.

When the Upper Sixth was formed and separated from the Lower Sixth, Mr. F.N. Gibbs became our teacher. He was extremely strict. If we made a mistake in our parsing we stood up on the form. If we could give a reasonable excuse we were allowed to sit down. If the mistake was simply due to thoughtlessness we got a cut with the cane. The same applied to Arithmetic. It was most effective. At the close of a lesson, very few were left standing on the form.

Mr. Gibbs also held night classes in the city preparing teachers for their exams. I was employed by him to check the test papers in Latin, Euclid, and Algebra, write out the correct answers, and then, by what was called a jellygram, reproduce enough copies to supply the students. For the work I received one shilling per hour, the normal wages, at that time, of an unskilled labourer. But Mr. Gibbs’ partner objected, as he was afraid that I may replace him as a partner. So Mr. Gibbs dispensed with my services.

It was said that Mr. Gibbs made 800 pounds a year out of his Teachers’ Classes, but he received only 156 pounds a year from the Education Department. 800 pounds per annum was a considerable sum in those days. Mr. Rowe received 19 pounds per month (220 pounds p.a.) Mr. Hayden, the first headmaster in the State received 44 pounds per month (528 pounds p.a.) which was considered princely. So that his coaching classes brought in over 50% more than the leading Headmaster in the State.

Under Mr. Gibbs I became the Dux of the Upper Sixth and presented with a silver medal the size of a shilling. At Combined School Sports there was an inter-school tug-of-war, eighteen boys a side. Mr. Hayden bought twenty medals (they had been struck by the score), eighteen for the winning tug-of-war team, leaving two over. One was presented to me as Dux, the other to the leading girl.

One another occasion, being interested in a talk that Mr. Rowe had given us on the digestion of ‘food in the human body’, I wrote an essay on “Tracing a bit of bread and butter from the mouth into the blood.” Mr. Rowe was delighted with it, showed it to Mr. Hayden who, after a sonorous speech, presented me with a little black book costing 1/-. The day of school prizes had not yet dawned.

There were many nice friendly girls in the Upper Sixth. Among them was Muriel Frith, whose golden hair hung down to her waist. She eventually became the wife of my pal, Charlie Whittaker. I liked all the girls, but loved none. I would pick out a girl that was likeable, find a poem in Wordsworth or some other poet dedicated it to say “Mary.” I would copy the poem on a piece of paper entitle it to the girl I had in mind, draw butterflies all around the edge, and fill them in with coloured crayons, and then hand it to her.

After tea one night, having done my school exercise, I was busily engaged on one of my butterfly designs, when my Father leaned over saw what I was doing, and confiscated the illustrated poem. He folded it up, and put it in his waistcoat pocket. The next time I saw it, it was worn through at the folds. He must have shown it to every man who came into the quarry, and I guess they all laughed heartily.

After that, I copied out all such effusions and illustrated them in the secrecy of my bedroom.

As a young boy, like all other boys of my age, I had a “shanghai” often referred to as a “ging.” On holidays three of us would walk up to Campbellfield each armed with a “ging.” Campbellfield would be some five or six miles away, and was open country, full of gum trees and briar bushes and birds. We were little heathens, taking a pot-shot at every bird we saw, especially little yellow rumped tom-tits. We climbed the trees, bird nesting. I shudder when I think of it now – with legs astride a lofty horizontal bough, riding out, as it were, to a magpie’s nest at the end, popping an egg into my mouth, riding the bough back, and then sliding down the trunk, disgorging the egg, and blowing it to take it home. It was a real day in the country.

Then I used to shoot at sparrows around the house. I remember standing under a pepper-corn tree next door, when I saw a sparrow sitting on a bough right above me. I took sight, pulled my ging and the sparrow fell dead at my feet. For a moment I was elated at my skill, but, as I stood with the dead sparrow in my hand, I was overcome with remorse.

So I dug a hole in the front garden, and sadly lowered the dead sparrow. The eldest boy next door was a monumental mason, so he gave me two small slabs of marble, about six inches by two inches. I placed one horizontally over the grave, the other vertically at the head. I was sad at heart. I had taken a life and despite all my desires, I could not give it back.

I never shot another bird.

I am convinced that the State School gave me a grounding in education as good as any college could have done. It may be, from the professional point of view, a boy may gain more clients from his mates at a College, than he would from a state school, but I doubt even that. Only one member of my staff, Una Harrison, attended a college, (M.L.C.) and she is a credit to her college. My two senior Partners attended Melbourne High School, and my secretary attended the equivalent High School for girls. They all possess as much character as any others I have met.

It was a privilege recently to address the senior scholars of Camberwell Central State School at their Assembly. I have never met a better behaved set of children anywhere, and when it came to question time, they displayed remarkable intelligence.

As for Sport, I was amazed when the various Captains (both boys and girls) read out the results of various team matches, and also particulars of coming fixtures. This would be very nearly as good, I should think, as any Public School, and certainly very much better than in the State Schools of my day. None need fear the adequacy of State education (including coverage of Sport), nor doubt that State School scholars will not win as many honours and as many scholarships as those attending Colleges in these days of wider opportunity.

When I was fourteen years of age, I won a scholarship which entitled me to attend the University High School at half fees. This was not the day of scholarships in plenty for only two were awarded that year for the whole of the area north of the Yarra. But our economic circumstances were such that I was unable to accept. This was after the crash of the land boom in the nineties. The whole national economy was at a standstill. We were greatly affected at once, because the almost complete stoppage of building and road-making meant that little or no stone was needed. My Father’s earnings fell from 15 pounds per week, to one pound a week, and then stopped altogether.

My brother Jack had been apprenticed as a carpenter and joiner and as building was now non-existent, there was no work for carpenters. So he was compelled to start his business life all over again. He became apprenticed to Tom Passfield, a wealthy baker and pastycook. Passfield was a prominent Church Member in our Sydney Road Methodist Church, but was not a generous employer. Jack worked ten or more hours a day, and worked the clock round in preparation for Good Friday – hot cross buns, and all for the miserable pittance paid to apprentices in those days, and with no bonus for overtime.

Jack was a splendid brother. He had a beautiful baritone voice, and sang in the Church choir. He was a first-class carpenter and cabinet maker. We still have a little china cabinet he made for me. When I was married he made for me a side-board in silky oak – a fine piece of workmanship, but when we moved from Cherry Road, we had no further use for it, so we sent it to “Decoration” for sale by auction. It brought the abysmal price of 30/-. It greatly distressed me to think that Jack’s beautiful workmanship was valued at such an insignificant price, but sideboards were then out of date, and a drag on the market.

As a pastry-cook Jack was marvellous. I have never seen anyone move as quickly to make such appetising dainties. He eventually bought a restaurant in Collins Street (right opposite George & Georges drapery emporium). It was called “The Barbison” and was frequented a good deal by Artists. A three course dinner cost 1/6, and a splendid dinner it was. But it did not pay, and had to close down.

Jack went back to his trade as a carpenter, then went to Perth for a while, eventually moved to Sydney, living with our sister Ethel. Here he married “Lottie” and had four beautiful children.

Poor old Jack, he became very deaf and developed Parkinson’s disease. At this time, I used to go to Sydney every month as a Director of the City Mutual and generally I called on Jack and Lottie, who always amiably made me very welcome. When Jack died I did not feel equal to going to his funeral, though I have regretted it ever since. Jack never had the chances I had. His forced change of occupation gave him a chequered career.

It was not long after that, that my Sister Ethel went to Perth to keep house for my Father and Jack. Here she met her future husband, Joe Simmell, also a carpenter who worked with Jack. Jack brought him home to tea, where he met Ethel. Joe was a fine fellow, a true Englishman. He doted on his wife, and was a splendid Father to his two sons, Basil and Reg.

While Father and Jack and Ethel were in Perth, there were only three of us left at home – Mother, my eldest sister May, and I. We depended mainly on May’s salary, 30/- a week. Fortunately the house was paid for, so there was no rent or interest to meet. May worked in a drapery store, firstly for a short time in Brunswick then in Ball & Welch, then situated in Carlton, later moving to Flinders Street, City. While in Brunswick she worked until seven o’clock every night, and ten o’clock Saturday night, which was the shopping night of the week. Sydney Road would he crowded with people, spilling over onto the road, so that the cable trams could proceed only slowly clanging their bells all the way.

Remittances from W.A. were erratic. Every time the postman came with a letter which bore the W.A. stamp we would ask him in, and give him a hot Cornish pastie, which he greatly enjoyed. I have never tasted a Cornish pastie equal to those Mother made.

As work petered out in Western Australia, it was not long before Father and Jack and Ethel came home. From then on, the family income was pitifully small. Jack got a little work as a carpenter, Father got odd jobs, Ethel stayed at home to run the house, as Mother suffered greatly from rheumatism. The whole family mainly depended on May’s salary, which was the only regular income.

Father got very despondent – there were no unemployment allowances or old age pensions in those days. I can realise now that my Father must have been very conscious of his inability to earn any money, and he must have suffered acutely. His mind must always have been at tension. Unemployment was the shadow that hovered our home. As a result, it was determined that I should become a Government Servant, and so be in constant work. The only Government Department open to take on employees at that time was the Education Dept., which needed a small supply of junior teachers. Under Mr. Rowe, I prepared for the half-yearly exam for our school, got top place, but there was no vacancy. Six months later there was another exam I again came top – but again no vacancy. By this time Father was feeling desperate, and he told me he saw a notice at the local wood-yard advertising for a boy at 7/6 a week. He suggested I should apply for it. Buy my Sister May, most emphatically protested. “You know,” she said “we have always made up our minds that Os would be a Civil Servant, and so have constant employment. If you do not agree, I shall leave home and take him with me.” How she was to keep herself and me on her small salary, I cannot imagine. But, worse still, how would the family manage without it. My Father gave in, I sat for the next exam, again got first place. This time fortunately there was a vacancy in my own school. I started as a Monitor in the teaching profession at a salary of 1 pound per calendar month, (about 4/7 a week). This solved one of the most important problems in my life – getting work.

There was another problem now appearing on the horizon. I Remember one day walking up the yard at the back of the school when suddenly a question flashed into my mind – “Why am I here? What is it all about? What is the whole purpose of life?” I had begun to think.

It is strange that children are instructed for the period of their school life. Necessary knowledge is pumped into them so that they can read and write and a little more. Then, at the age of 15 for 90% of them all education ceases. Their period of instruction is finished, now they need to be educated, to be taught to think. But they then go into a repetitive job, which after learning the mechanical technique necessary to do their work, makes little or no demand upon their thinking ability. They remain for the most part, uneducated, they not been trained to think.

It seems to me that State School should be open at night, with a fresh batch of teachers so that the elder children who go to work, could now attend the sort of class they wanted – in art, of music, or playing the drum, or science or just anything they wanted to learn. This would be the period when they began to think and the old school would become their “Alma Mater,” and help them to understand life in their most strange and difficult days. Not only would a new life be opened up for them, but many of them would find an outlet from boredom, and have no need to join with high-spirited youths and lasses, who bored to tears, find an outlet for their energies in “bodgies” or similar bodies.

I was appointed as a Monitor in my own School, Albert Street, Brunswick, on the 20th August, 1898 and was immediately given a class (of about 60 little folk) known as the Upper A.B. The three lowest classes in the school were known as the Lower A.D. (or Babies), the Middle A.B., and the Upper A.B. All three classes met in one big room, the Lower at the East end, the Upper at the West end (each in a slightly sloping gallery) the middle class on floor level between the two galleries. Altogether there would be about 200 children in the room.

I rather enjoyed this teaching, but it did not last long. I was moved into the room where the next grade met (called the First Grade) consisting of the Lower First, the Middle First and the Upper First.

I was seldom given a class to teach. On one such occasion, I was teaching the Upper First, the old poem about the “Busy Bee.” The children were repeating the line “When the sun is hot, they linger not.” Just at that moment the Head Teacher entered the room, and told me in a critical voice, I should question the children to see if they understood what they are repeating. So he turned to the class, and asked in a dramatic manner, “What is it that the bees don’t do when the sun is hot?’ One bright youngster replied – “Please Sir, they don’t swim.” The Head Teacher was discomforted, but I was delighted.

I liked the actual teaching, but the Head Mistress of the room, an old maid of the Victorian pattern, with a wrinkled face, and a high colour, would call from one of the classes what were called the “weak readers,” children who were not far above the moron type. “Take the weak readers, Oswald” the Head Mistress would say, and thereupon a dozen of these sub-normal children would gather round a table, and we would start “The cat sat on the mat” and I would spend half-an-hour trying to teach them to read. There the dozen children would be changed for another dozen “weak readers” and on I would plod, the most monotonous and the most depressing job in the world. The children instead of learning to read, after a while, with constant repeating of the words, would learn them off by heart, and then associate them with the picture on the top of: the page. If they made a mistake and associated the wrong reading with the picture, they would recite the page they had memorized belonging to the same other picture. It was just hopeless.

I simply hated it all. I remember telling my Mother “I would rather break stones on the road side than teach.”

When I think of the way teachers are trained today, I sigh with regret for my past. I understand that today teachers can go to the Training College, and while there, are paid 8 pounds to 10 pounds a week. I would have loved to go to the Training College, but in my day, I should have had to pay 2 pounds a week for the privilege. Fancy doing that on 4/7d. a week!!!

At this time I had chestnut hair familiarly called “ginger.” Also I lisped. Realising that the combination of these two things would easily make me the sport of the children, I determined that, as I could not change the colour of my hair, I should do my best to overcome the lisp. And so, in the right-of-way at the end of our street, (I can shut my eyes and see the spot now) I began to say aloud, “I muth not lithp” and kept on saying it until at last I won, and could say quite clearly, “I must not lisp.”

Before I conquered the lisp, I used to recite: “How Tom Thawyer got hith fenth whitewhathed.” It used to bring down the house.

Much to my gratification, then it was realised that it was the “lispth” that was the attraction.

After a year with the weak readers, I was moved up a grade – to the second classes. These were four classes housed in a hall a quarter of a mile away belonging to the Church of England. Having a class on my own was a Godsend. On singing afternoons, the green baize curtains separating the four classes would be drawn, aside, and the four classes would cluster to the centre, and one teacher out of the four of us, would stand on a table and take that singing lesson.. This I thoroughly enjoyed. I had recovered from the nightmare of the “weak readers” and was beginning to find my feet.

The following year, I would be about 17 years old, I was moved back to the main school, and given the fourth “Third Class” to teach, and had a classroom of my own. It was in the form of a gallery, the seats rising tier above tier to the top row. The children in this row were silhouetted against the windows, which was very trying on the teacher’s eyes. I was very happy with my 70 children and I think they were too.

Once a week was drill afternoon. I would take about 120 boys out to drill. This was extremely trying, a line of 120 boys stretches a long way. While I would be marshalling the boys at the top end, the boys at the bottom were playing pranks. I would rush down to them, but while I roared at them, the boys at the top would then play up. At the end of the afternoon, I would not be able to speak above a whisper.

But I greatly enjoyed my own class, the fourth Third. We were all very friendly and I had so won their confidence that there was no necessity to use a cane.

All this time I was studying for promotion, as Pupil Teacher, sitting for one exam each year, thirteen subjects each time. I moved up from Monitor, as soon as I passed the first exam, to Third Class Pupil Teacher, and my salary rose from 12 pounds to 20 pounds per annum. Latin, Euclid, and Algebra were then being introduced into Teachers’ exams, and those passing what was called the “New Programme” received an extra 10 pounds p.a.. I elected to go for the 2nd Class P.T. “New Programme” and was raised 20 pounds to 40 pounds p.a.

In this latter exam, my Latin paper was lost. Suspicion fell on me that I had not sent one in, but Mr. Rowe stoutly insisted that I had, and I was therefore given the privilege of being permitted to sit for a supplementary exam. Mr. Rowe kindly gave me extra tuition. After the final lesson, I thanked him and said I was pretty certain I would get a pass. He replied “of course, but you must get 100%” and to my surprise, I did.

In 1901 I passed the exam for the 1st Class Pupil Teacher (New Programme) at a salary of 60 pounds per annum. After twelve months I would have become eligible to become Head Teacher at a small country school at approximately 100 pounds p.a., depending partly upon the result of the children’s annual exams, and the Inspector’s report.

As I was a bread-winner upon whom my family partly depended, I could not afford to go to the country, and pay board while there, which would leave little to send home.

So I studied for the Clerical Division of the State Civil Service. My word, I did grind for it. The economic pressure behind me made it a necessity for me to succeed.

As I look back, I am glad that I was born poor. Had I been born rich I should not have had behind me, always prodding me on, the thrust of economic necessity. I knew that, unless I studied consistently, I should not pass my exams, and would lose the opportunity to get fitted for a position requiring intellectual training. So poverty behind me inexorably pushed me on.

My memory was excellent in many respects (particularly in the memorising of dates, and events, and such like) but it often failed in practical matters. On the day of the examination for the Clerical Division, after I arrived at Wilson Hall where the examination was to be held) I found that I had forgotten my entrance forms on which was my number. I cycled home at top speed (over two miles) and arrived back twenty minutes late, all hot and bothered.

Eight hundred sat for the exam, (400 of whom I was told were school teachers) for 30 vacancies. I was fortunate enough to be successful and was appointed to the Office of the Master in Equity and Lunacy (situated in the Law Courts) in March 1903. My appointment was to the Lunacy Office, which proved to be a wonderful office, for it was staffed by splendid men.

Owing to the Governments recurring policy of retrenchment, there had been no Civil Service exams for 15 years, so practically every man in the Office was at least 15 years older than I was. As I look back, I realise I owe them all a tremendous debt. They were all very capable, very friendly and took great pains to teach me the work.

The man immediately above me was Arthur Donahue, a devoted Roman Catholic, and a man in every sense of the word. Full off common sense, he was very able and without the shadow of a turning. I was in the Office only a few months when I caught Scarlet Fever. The very first day I was away, he walked from his home, two miles away, to come and see me. No wonder I had for him a very deep affection.

All appointments to the Service were for a probation period of six months. However, just when my probation period had expired the Premier, William Irvine, (known as the Iceberg) decided that no more probations were to be approved. I went in to see the Master, Thomas Prout Webb, and he told me he was sorry, but I was sacked. This was a staggering blow. Here I was, 18 years of age, and out of work. As I had been impelled to resign from the Education Department when I entered the Clerical Division, that Department refused to take me back. A friend in the Crown Law Department asked me if I knew Willie Watt, the State Treasurer, or his partner W.H. Edgar. I know neither, but being a Methodist, I knew Mr. Edgar’s brother, the Reverend A.R. Edgar of Wesley Church. So I went to see him and told him all about it. The result, was that the few probationers concerned had their appointments confirmed, though I guess none of them knew how it happened.

My salary at this time was 40 pounds p.a. (I had dropped 20 pounds p.a. to enter the Clerical Division). On confirmation of my appointment, I was raised to 50 pounds p.a. (nearly a pound a week). As I paid all my salary to my Mother, (excepting fares and a shilling or two pocket money) my finances were very tight.

I remember walking up Lonsdale Street one day after lunch, when I felt something hit my shoe. There was a hole in my trouser pocket and a 3d. bit, my sole wealth, had dropped through. it rolled along the footpath, until spied by a passing gentleman, who put his feet on it, picked it up and promptly put it in his pocket. He was one of the firm of Michaelis & Hallington, the rich leather merchant. I was too shy to ask him for it.

As I had finished with teaching exams, I conceived the grandiose idea of writing a history of England. To this end I read every historical novel upon which I could lay my hands. I made careful notes on the books of old Sunday School lesson papers, safety pinned them together, and hung them on a string under my dressing table which consisted of a wooden packing case covered with cretonne.

I got so far with the idea that I actually wrote the first chapter or two in a black covered exercise book. I determined to illustrate it myself, pirating the illustrations from old history books. There was nothing original in it, neither in the text or in the pictures. I got so far as the Roman invasion of Britain, and then petered out.

I travelled to work from Brunswick on the cable tram which went from. Moreland Road, North Brunswick to Flinders Street, Melbourne, a distance of over four miles. The fare was two pence each way, but reduced to three pence return if on the trams before 9 a.m.

As I passed the University, it used to amaze me to see University students old enough to have moustaches, and here was I, very much younger, compelled to go to work. They lived in another world, I thought I would never be able to enter the University. But my chance came when I was a married man with four children, and I was 42 years of age.

While I was a teacher, I had injured my hips in a couple of bicycle accidents, with the result that standing was particularly tiring. As there was much standing in the Lunacy Office, which made my hips and my back ache (taking down files from their pigeonholes and putting them back again), I asked to be transferred to the Equity side of the Office, where I could sit down, Sitting down as much as possible has been a necessity from boyhood on, and has had a considerable influence on the course of my life.

The room to which I was allocated was the “Searching Room,” in which were kept all the files relating to Probates and Letters of Administration. The papers (excluding the wills) relating to deceased estates were filed away in rows and rows of pigeon holes. They were of course, carefully indexed, and anyone wishing to examine the will of a testator, or the papers relating to the affairs of an intestate, paid a fee of 2/6, searched the index for his particular matter, obtained the number of the file, when a clerk would produce the necessary papers.

There were many amazing wills. One testator, a sailor, scratched his will on the lid of an enamelled tin box. Probate was granted to it, because as he was on Active Service; his will had not to be witnessed.

It was amazing to discover the number of people who were afraid of being buried alive, and who requested in the will that a vein in their body be severed before burial. Some wished to be buried with a favourite dog or cat, though I doubt whether this directum would be fulfilled.

One testator evidently thought very little of his two sons. in his will he wrote “To my son – I give a shilling to buy a rope, he will know what to do with it. To my son – I give the sum of one shilling to buy a Bible, the best treatise on truth I know.”

All wills were kept in the strong-room, but were first copied in huge books, and it was my duty to make a copy of the wills, about 3,000 a year. Some were short and simple, some were extremely long and involved, and took many hours to copy. Two clerks would compare the copy with the original, one reading from the original, the other checking the copy. The verbiage often consisted of phrases, in fact long paragraphs, taken from the Trust Act, and incorporated in the will. Checking became a tedious business, and the checkers resorted to various devices to hasten the examination. All common phrases were condensed by using the first letter of each word. For instance, “last Will and Testament” became last WAT. “After payment of all my just debts funeral and testamentary expenses” (a stock phrase in almost every will) was condensed into “after PAT of all my J DS FAT EXES” Nevertheless it was a tedious and monotonous job.

After some little time, it was decided to type the copy wills and I became the first typist to do so. Learning the “touch” method, I sat in my seat beside a window, typed away, and while so doing spent much time in looking out on William Street, up the centre of which was a horse-driven cab rank. It was interesting to watch, for as one cab drove off, all the rest moved up one quite automatically. The story is told of a prisoner condemned to die. When he was asked to choose his last meal, he asked for sausages. When they were placed before him, he refused to eat them, saying they were made from cab-horses. “How do you know?” he was asked. “I’ll prove it!” he said. He cut one sausage into eight small pieces, removed the first piece, and all the rest moved up one.

At this time, there was an old Cornish cab-man, who lived near us. He was a fine old fellow, very religious, and had three enthralling interests, flowers, music, and children. As his back yard was bricked over to make a washing-stand for his horse, his garden consisted of a row of kerosene tins, in which he grew brilliant geraniums. For music he possessed a tiny harmonium on which he used to play his favourite hymns. He had no children so he had pulled some palings off the fence dividing his back yard from his neighbours so that the child next door could frequently come in and see him.

He had grown to manhood without being able to read or write. While a miner in Bendigo, his mates took him in hand, and during crib time, they traced the letters of the alphabet on the clay. He really graduated with honours, for not only could he read the newspaper, but novels as well. The masterpiece of all literature to him, (other than the Bible) was “Barriers Burned Away” by E.P. Roe.

His spelling, as was to be expected, was entirely phonetic. One night coming home in his cab, (fare threepence from the City to East Brunswick) he started to quote the Biblical Alphabet.

“A is for Adam, the Father of our race.” He got as far as “F” and was stumped. “I can’t remember what “F” was for” he said, “unless it was for Pharaoh.”

In the Searching Room (more familiarly known as the Long Room) my Chief, James Carter, was one of the finest characters I have ever met. He was very able, and extremely kind. He was a Lay Reader in the Church of England, and was so helpful to everyone that he was one of the most loved men in the whole office. Sometime after he lost his wife, he became engaged to a very fine woman, Miss. Hamilton. They were much in love with each other, and just before they were to be married, she unfortunately became ill and died. This was a great blow to Mr. Carter, but he met it with characteristic Christian faith. After he retired, he contracted cancer, and I went down to his home in Hampton to see him. He was delighted to see me, and wistfully asked me could he call me “Os.” I was overjoyed by his desire to do so, and his request somehow strengthened the bond between us. In the office the clerks (except the juniors) always addressed each other as “Mister"! It may be a barrier to real friendliness. Personally, I love to be called by my Christian name. It removes all barriers.

Of the three most popular men in the Office, two were Roman Catholic (Arthur Donahue and Thomas Kelly, of whom I shall speak later) and Mr. James Carter, an Anglican. All three were practising Christians and admired by the whole staff. To them I owe much, not only for the way they taught me office routine, but also for the simple straightforwardness of their characters.

Our parents had always brought us up to attend Sunday School and Church. We attended the Sydney Road, Brunswick, Methodist Church. Remember, these were the days when Methodism was booming. The Church would hold nearly 800, and in order to get a seat for the evening service, one had to be there not later than five minutes to seven. Alas, times have changed. I understand the evening congregation does not exceed 75 to 100. Brunswick is full of migrants, and once a month, a service is held in Italian for migrants, which shows one attempt to meet the needs of an alien population.

We had some notable Preachers. Rev. Alexander McCallum was loved by everyone. He was a most kindly man, entered into everything with remarkable zest, and was a splendid preacher. During his appointment to the Sydney Road Church, we passed through a deep depression, following the burst of the fantastic Land Boom. People went mad buying up land, and prices rose astronomically. Buildings were started, houses and hotels were built, and we lived in an aura of imaginary prosperity. And then the Boom burst.

Of course, the working man suffered most. Unemployment was tremendous, and our family was caught in the maelstrom. So was the Church, Rev. McCallum received, I believe, 200 pounds p.a. as stipend, but the Church was unable to pay it, and Mr. McCallum went short without any complaint whatever. We held an exhibition in the school buildings for the purpose of making up the leeway. The Exhibition remained open for three weeks, and from memory, I think Mr. McCallum’s stipend was eventually paid in full.

By a strange coincidence, Dr. McCallum’s son, Colin, is a joint Treasurer with me at Wesley Church. He was the Chief Librarian in the Public Library, and is a very fine Christian gentleman, he was awarded an O.B.E.

In my late teens and early twenties the Rev. G.S. Wheen was our Minister. At first sight he seemed rather austere, but it was not long before he won the admiration of everyone, and in particular the affection of the adolescents. He was a magnificent Preacher, very scholarly, but down to earth.

He started a theological class for the young men and I am very grateful that I was a member. Among the members was one, Harrison Chadwick. One night, on being asked to pray, he asked “0 Lord, help us to get this theology into our heads, and when we get it in, help us to keep it there.” It was very fitting that Harry’s son is now a Methodist Minister in this State.

My Father was a strict Sabbatarian. We had a beautiful bush of Daphne, but if we wanted to wear a piece on Sunday, we had to pick it on Saturday night. (This was founded on the incident recorded in the New Testament where the Disciples plucked the ears off corn. on the Sabbath, which was a breach of Sabbath observance. But the Lord excused it because the Disciples were hungry and needed food.)

We were not allowed to travel on trams or trains or even in a horsedriven vehicle on the Sabbath, as that would be breaking the Commandment. If we wanted to attend the Wesley Church in the City, we walked there and back, a distance of between six and seven miles.

Until the trams came, we travelled to town on week-days by bus fare 3d. which you placed in a glass box behind the driver on the box seat. If you wanted change, you poked your hand, with the money in it, through a hole at the side of the fare box, and ring a bell attached, when the driver would give you change.

When the cable trams came along Rathdown Street, the big buses were scrapped, and a miniature box (called the pill-box) carried the tram passengers from the terminus at Park Street, as far as the Lyndhurst Club Hotel in Albion Street. The Driver was Mr. Buggy.

Our Sunday School building was the best designed I have ever seen. The Assembly Hall was built in the form of a semi-circle, the classrooms with folding doors, opening off the semi-circle. There was also a gallery with class-rooms opening off it, a replica of the classrooms below, so that each class had a separate, self-contained classroom. At the opening of the service, the senior scholars met in the Assembly Hall, and the juniors in the gallery. There was a rostrum in the centre of the radius of the semi-circle, and as it was about six feet high, the Superintendent had complete control of the scholars, the seniors six feet below him, the juniors a little above his eye level.

Facing the back of the rostrum was the “Lecture Hall” where the young men assembled for the opening service. After ‘the Assembly sliding doors were moved across, making the Lecture-Hall into a self-contained class room.

When I was about seventeen years of age, I became the junior Secretary of the Sunday School, firstly under Will Roberts, our old postman, later under Bernhard Trahair, a draper with a flourishing business in Sydney Road. He was a delightful fellow, with a pink complexion, and married Annie Wilson, the older sister of Arthur Wilson, one of my best friends.

There were over 800 scholars in the Roll of the Sunday School, and the average attendance was 554.

After Sunday School was over, I used to ride my bicycle across to Princes Park by myself. I was a shy and lonely boy, and had not yet made any companions. When I did the whole aspect of life was changed.

There is no doubt that the Sunday School is a fine place in which young people can gather. The best marriage market in the world. Young men of high ideals met young women of a similar type, and Cupid took over and did the rest.

Six of us young fellows came together, Charlie Whittaker, Arthur Wilson, Arthur David, Norman Ford, Ralph Coade and I. We formed a group which we called “The Fairies.” Every Christmas we went for a camp over the holidays. At one camp, our Minister, Rev. J.G Wheen, came up to join us for a day and a night. I can, in my imagination see him now, walking into the camp, our tent being pitched on the banks of the Watts River, Healsville. He was carrying an oblong wicker basket with sloping sides and a lid across the top fastened down with a little peg of wood pushed through a small hoop. It was full of goodies packed by a thoughtful Mrs. Wheen. Our tent could just comfortably hold five. When Mr. Wheen came in to sleep he claimed an outside position, with the result he was less than half-in, the rest of him being well out. He said he did not sleep a wink all night, and we believed it.

One of the men who had a tremendous influence on me was Mr. Fred Straw, He had a draper’s shop in Sydney Road, but he had the soul of an artist. His wife was a lovely woman, and, to a great extent, took somewhat the place of my Mother in my admiration, and completely won my heart. Her influence was both profound and sweet.

The Straws had four children, Eric, the eldest became the first member of the Knighthood of Christ, which I shall describe later. He later followed in his father’s footsteps and became a very successful draper – now practically retired and living at Emerald. Keith was next, a handsome boy (reminding one of Millars paintings (Bubbles) used to advertise Pears Soap). He was very quiet and courteous, had a fine brain, and became the head of the Explosives Department. He died of cancer in the pancreas.

Three more of the Fairies, Charlie Whittaker, Arthur Wilson and Arthur David, also became Teachers, Norman Ford became the Secretary of the Sunday School. The scholars were normal boys, but as they began to enter adolescence, there were some pretty wild ones among them.

One Saturday evening I arranged for the members of my class to come to our home for tea, as my Mother was a splendid cook. The boys sat down to a wonderful tea at 5 p.m. and went solidly until 7 p.m.

“Have a bit of this, Bill. It’s great!”

“O.K. I’ll have some of that next.”

And so it went on, until my Father declared at 7 o’clock, he wanted his tea, and the boys and I adjourned to the “front-room.”

Next Sunday afternoon, one of the boys was giving great trouble in class, and refused to stop talking. I told him he would have to say no more, or leave the room. He left, and outside the class room window, he began to pass uncomplimentary remarks. One boy, Bill Cruickshank, said “Fancy talking like that, after all he was at your place last night. I can’t stand it any longer – I’ll settle him.” And with that Bill left the room. What he did, I do not know but there was complete silence from outside after that. The noisy offender, in later years became a Captain in The Salvation Army.

On Sunday mornings a Children’s Service was held at 11 o’clock in the Assembly Hall of the School. The first man to organise his was Mr. A.B.C. Harris, a very energetic man, with a great capacity to interest children. Later, he was followed by Mr. Robert Agnew an extraordinary man, a most dramatic stony-teller, who could simply entrance the children.

It was here that Charlie Whittaker and I began our appearance in public. Charlie was a born wit, and a very clever speaker, and could hold children in a perpetual simmer of mirth. My function was to give short addresses, illustrated by lightning sketches in coloured chalks. These became so popular that for many years, I was requisitioned for children’s Anniversary services in various Churches.

It was my custom to give the sketch after the service, to the child who read the lesson. In order to be seen at a fair distance in the dim light of a Church, the sketches naturally had to be very bold and rather crude. The children’s imagination would fill in all the details. A smear of yellow across the foreground to portray Spring in England so worked on the imagination of one little girl that she declared she could see the daffodils.

But one boy, coming up to the platform after the service to claim the sketch, as soon as he got near, his face fell, and he sadly said, “Don’t it look different Mister, when you get close to it.”

Which reminds me of a very funny incident. I had been taking the service in our own Church at Canterbury, and after the service, was introduced to a lady from Brunswick, my old home town. As she shook hands with me she said, “We heard your son preach this morning.” I told her the story of the boy and the lightning sketch, and added, “Don’t I look different when you get close to me!” (Like the boy felt when he got close to the lightning sketch).

I started going to Sunday School at the same time as I attended the State School, when I was 4½ years old. As the Church was a mile away from home, and though it was before the day of cars, we went to morning school at 9.30 a.m., stayed to Children’s Service in the School Hall at 11 a.m., came back to Sunday School at 2.30 p.m. in the afternoon, and when we were old enough, came back to Church at 7 p.m., the evening Service being followed by a Prayer meeting. Sunday was a full day, rather exhausting, but we loved it.

I have already mentioned that my Mother was a splendid cook. When the Church Anniversary came round, my Mother cooked generously for the usual tea meeting. Jam tarts, custard tarts, and pasties all by the dozen were packed into a large wicker clothes basket, carefully covered with a tea towel, and Ethel and I, each taking a handle would deliver the basketful of delicacies to the Sunday School.

Being Cornish our relations in Cornwall always sent us a packet of saffron, so we always had saffron cake at Christmas.

Custard tarts and jam tarts were commonplace to us. At day school in the lunch time, Billy Reid and I sat up on the cross beams of the play shed to eat our lunch. I swapped my custards and tarts for his German sausage sandwiches. it was a satisfactory arrangement, for it was to each of us a very definite change in our menus.

Billy was a handsome boy, black eyes, long eyelashes, a pleasant face, in fact rather a modern Apollo. The last time I saw him he was driving the local rubbish cart. Our roads had divided after school days.

At the relief of Mafeking (during the Boer War), there was great excitement in Melbourne. Crowds paraded the streets and trams were lifted off their tracks.

My brother Jack celebrated by taking me to the theatre for the first time in my life. Now the theatre was looked upon askance by the Methodists of that time. I was very perturbed – what if Christ came when I was at the theatre?

But I soon banished my fears. The play was a Comedy – “What happened to Jones!.” I completely forgot myself and roared with laughter. The people around me laughed at me, I was so uproarious.

Playing cards were also forbidden at home. As they were so often associated with gambling, they were looked upon as the Devil’s playthings. But the whole family was infected with card fever (Mother only slightly) but Father was in strict opposition. So that our cards would never be discovered, Jack built a secret drawer in our wardrobe.

Father was President of the Brunswick and Coburg Fowl and Canary Society. On the night that he was planned to go to a Canary Show, we arranged to have a domestic card party, particularly for my benefit. I think it must have been my birthday. But I had the ‘flu. I got out of bed to play, but couldn’t take it. I had to go back to bed again much to my chagrin.

Unexpectedly, Father came home early. The players foolishly scooped the cards into their laps, and then Father gave them a lecture on the evils of card playing, concluding with “It’s all for Oswald’s sake.” Little did he know, that every afternoon after school, I rode my bike down to my brother’s cafe in Collins Street, and played cribbage with the Caretaker.

I had a passion for cards then possibly increased because they were forbidden. Study pushed cards into the background, and only recently have I played “Five hundred” again, and thoroughly enjoyed it. But I have never played for money.

As for dancing, that was strictly taboo – Harry Robin (our Sunday School Superintendent at Canterbury) and I went away together for a holiday. After the evening meal, the guests engaged in dancing. Harry and I sat on the side-lines and watched. Many a girl took pity on me and asked me to dance. My reply was always the same, “I don’t dance, thank you.” “But I’ll teach you.” With that stubbornness of a typical Methodist of those days, I would reply: “You can’t teach me.”

One day as we were out walking, I said to Harry, “I think we are a pair of fools. We damn dancing, but we don’t know a thing about it. I’m going to ask those girls to teach us.” He agreed. So I asked the girls to come over after lunch and teach me to dance. They cheerfully complied. After tea, we adjourned as usual to the dance hall. A girl would ask me to dance. I would warn her about my ignorance. As my partner would try to engage me in conversation, I would say “Don’t talk, count one, two, three.” Before long the whole crowd was chanting “one, two, three” as they danced about the hall.

This cured me of a lot of priggishness and I am sure my influence on those girls was increased because I danced with them_. It had broken down the barriers.

The Church was strongly opposed to dancing, but things have changed in the last few years, and the prohibitions against dancing have been almost removed.

The Fairies became the Leaders, Local Preachers and Teachers of the Sunday School. Under the leadership of Mr. Straw, a preaching band was formed which took services in the local Churches and also in the Old Men’s Home at Royal Park. On one occasion at the Home, one of our younger men, Les Wilson, was to speak. Les stood up on the rostrum, and ‘opened not his mouth’. After a painful silence, I got up and gave out hymns. Les told me afterwards his mind became an absolute blank, and he could not think of a single word to say. Later, he became very successful as a speaker and Leader of the Young Men.

On another occasion, Charlie Whittaker and I were to take the evening service at our Moreland Church. We arrived early, the Steward was about to show us into a seat, when we told him that we were the Preachers. He drew back a step, looked us up and down, and then said in an aggrieved voice. “They always treat us badly.” Charlie and I felt like the Disciples when the Samaritans prevented them from entering Samaria, (you will remember they asked the Master to call down fire from Heaven.” We delivered ourselves with burning zeal, and held a Prayer Meeting after the Service, but with no visible results.

We had some exceptionally fine men as Superintendents of the Sunday School at various times. Mr. Will Harding was a Christian gentleman, and loved by all. Will Pearce was a Postman, robust and forthright. On one occasion, after urgently suggesting that the young men should not smoke, he turned to the girls and said, “Girls, see that your boys come to you with clean lips.” An unexpected burst of laughter completely dispersed the effect of his address.

Then there was Mr. Brazier, a big, strong man, with the gentleness of a little child. He was manager of Grundy’s timber yard. We loved all these men and they were a powerful influence with all of us.

Of all the people who influenced me for good, no one was more helpful than Charlie Whittaker and Arthur Wilson. It was with Charlie that I first became friendly. We both helped at the Children’s Service on Sunday mornings, and then, as Local Preachers on Trial, we together took services in the various Churches in the Circuit.

Charlie did not have the same privileges as I had for education.

He left school when he was twelve, and went to work. So, for some considerable time, after spending Saturday afternoon boating on the Yarra at Studley Park, Charlie would come home with me to tea. After tea, we adjourned to the “front room” and studied together. We did a fairly thorough course in English, parsing and analysing every line in Scott’s “Lady of the Lake,” as well as many other poems.

We also did the same course in Arithmetic as I had done as a pupil Teacher. They were very happy and helpful times to us both.

During the summer time, Charlie and I would take a batch of boys to the South Melbourne Baths to teach them to swim. I was never a good swimmer and as for diving, I was hopeless.

One Saturday afternoon I was determined to dive from the springboard. I was suffering from laryngitis but that did not deter me.

The waves were pretty high, and the troughs between each wave were pretty low. I stood on the end of the diving-board, took a deep breath, dived as the top of a wave was directly beneath, but of course missed it, and landed with a fearful whack in the trough.

The sudden immersion gave me a wonderful reaction. I swam around to the steps, and felt so fine, I determined to swim down into the shallows. Then I got a second reaction. I was overcome with a paralysing weakness, all my muscles seemed to collapse, and I could swim no further. So I trod water, for the first time in my life. When I grew tired I sank to the bottom, then came up again. The boys on the decking above though I was giving a display.

After going three times I decided to give up trying. Looking up I could see the sunlight glinting on the surface of the water, and I had almost an overpowering desire to give up the struggle. Drowning, when you give up fighting, would be a very peaceful death just like going quietly off to sleep.

I raised my hand, Bob Richards dived from the decking. Charlie Whittaker swam out from the shallows, and between them they pulled me out. I felt too sick on the Sunday to go to Sunday School, but was quite recovered on the Monday.

As Arthur Wilson was one of the Fairies, he joined up with Charlie Whittaker and me in many holiday jaunts, especially on the Yarra at Studley Park, as well as in our Christmas camps.

We all belonged to Mr. Straw’s Thursday night class, and had the same experience. When I entered the Law Courts in 1902 as a clerk in the Master’s Office, Arthur would come up every dinner time, and we both sat on a wooden form in the quadrangle, and ate our lunch together.

Years later, when the appeal was being made to rescue babies from the slums, Arthur joined and became a tower of strength. He and I generally took services together, and became known as “The Heavenly Twins.” I can never thank God enough for the friendship of Arthur Wilson, the finest man I have ever met.

The Sunday School anniversary was always a great occasion. A huge platform, capable of holding, I should think about 800 (there were 800 scholars on the roll) was built right across the East End of the Church. The front portion was on the level, and it was here that the seniors sat. Behind them the seats rose in tiers, until they reached the back wall. It was here that many hundreds of children sat.

For weeks beforehand the children practised special hymns after the Sunday School service, but the last couple of Sundays the whole afternoon was given to practise. The Anniversary continued over two Sundays, three services each Sunday, each one with a crowded congregation. Parents came, who seldom, if ever, came to Church any other Sunday.

The enthusiasm was tremendous. As usual with Methodists, a tea-meeting was held one night during the week, and that was always a great success.

Of course, Sunday School picnics were held every year – always on Cup Day. With a school of 800 scholars, it was felt to be to expensive to transport them by van or train to any distant picnic ground, seeing there were to many of us we were marshalled like an army, and marched, four abreast, down to the Sydney Road to Royal Park. Those who had a few pennies to spend would buy, before the start, either a coconut, some sweets, or a few early cherries.

Of course it was a gala day – buns served at eleven o’clock, the first sitting of lunch at mid-day – sandwiches and cakes, washed down with the most delightful drink, raspberry vinegar. Of course there were races for everyone in the afternoon – from the babies up to the Teachers.

Later on the School decided on a great adventure – to hire vans in which to go to the picnic. It was a scramble for the boys to get on the same van as their girlfriends. Coming home, they sang all the way. And the boys who had not any particular girl friend, sat on the tail board, and joined in the music by playing mouth organs.

It was a day of days, early and eagerly awaited every year.

I was tremendously in love and asked Elizabeth would she come up the river with me on the following Wednesday afternoon, the 14th June. She sweetly agreed. We met outside St. Francis Church in Lonsdale Street, and went by cable tram to Studley Park. We hired an outrigger at Burn’s boat shed, and rowed up stream. We came to a nook where honey suckle had twined over a small gum tree that was on the bank. We tied up to a tree under this little honeysuckle arbour, and sat together in the stern of the boat. I pleaded my cause earnestly, telling her I felt like King Arthur when he met Guinevere.

“For saving I be joined

To her that is the fairest under heaven

I seem as nothing in this mighty world,

And cannot will my will, nor my work

Wholly, and make myself in mine own realm,

Victor and Lord, But were, I joined with her

Then might we live together as one life,

And reigning with one will in everything

Have power in this dark land to lighten it,

And power on this dead world to make it live.”

I did not recite this to her, but very sincerely gave her the substance of it. Of course, she could not doubt my sincerity and consented, and we became the happiest couple in the world.

All the “Fairies” became engaged about the same time, and it was the custom on certain holidays, to hire a van to take the whole twelve of us to a day picnic. Later on, when we were married and owned cars, it became a car picnic. They were royal days six couples all in love – each knowing all the others thoroughly, and all full of fun and unselfishness.

Elizabeth had a lovely Mother. Her Father had been a cricketer, and, one Saturday afternoon, after making a great score, he threw himself on the ground to cool off. As a result he got pneumonia and died. He left two children, Frank and Elizabeth.

Times were hard, so Mrs. Hyett eventually married again – to Jim Sanders. They had two children – Myrtle and Percy.

Jim Sanders did not live very long, so eventually the second marriage only increased the inevitable financial burden.

From the time I knew her, Mrs. Sanders had her father living with her, Ephrain Pearce, a fine old Englishman – but past work.

Myrtle was a lovely little girl, of whom more later.

Percy was a headstrong boy. Both Frank and Elizabeth wanted him to get a better education than they had had. But Percy was stubborn. He had had enough of school, and wanted to go to work. So he became apprenticed to a copper-smith.

One day he was walking back to the coppersmiths shop, he saw a crowd of men gathered in the street. He pushed his way in, to find that a bull-dog had fastened its teeth into a little fox terrier, and the bystanders could do nothing to make him let go. So Percy lit his blow-lamp and placed it behind the bull-dog’s tail. There was a terrific howl, the bull-dog jumped into the sky, and bounded down the street.

But it was too late – the little fox terrier was dead.

The war put Percy out of work, so with thousands of others, he had to go to war to get a job.

He was wounded in France, and, as a result, he lost his left arm. Immediately we heard, Elizabeth and I banked 1 pound per week for him, so that he would have a little nest egg awaiting him, pending the effort the Government would make to rehabilitate its returned soldiers. He eventually got an invalid pension as a disabled soldier, so he was financially independent.

My father, who had been suffering grievously with asthma for six months, died in 1905. One night before he died, he sat up in bed, and sang, “Nearer my God to Thee.” He had a fine bass voice, and to hear him sing this wonderful old hymn in the very early hours of the morning was something I shall never forget.

His last years had been made very unhappy through prolonged unemployment. He felt his position keenly. He was a very capable man, and, if he had had the advantages of education, he would have been a great man.

He died when he was only sixty, quite worn out.

My Mother died five months after Father. She had peritonitis. On the Saturday the local Doctor said she would recover. so she requested that the whole family gather round her bedside on Sunday morn, and sing “Praise God from Whom all Blessings Flow.” But she took a turn for the worse early that morning, and when the Doctor called, he said she would not last the day. She knew all this, but still she wished us to sing “Praise God.” Our emotion was so great that it was with difficulty that we sang, but, controlling ourselves as well as we could, we did our best. Jack had a fine baritone voice, May was a soprano, Ethel a contralto, and Joe her husband, who was present too, had a fine base. Between us we managed to sing the Doxology to the end. Late that night my Mother died.